Database Tables

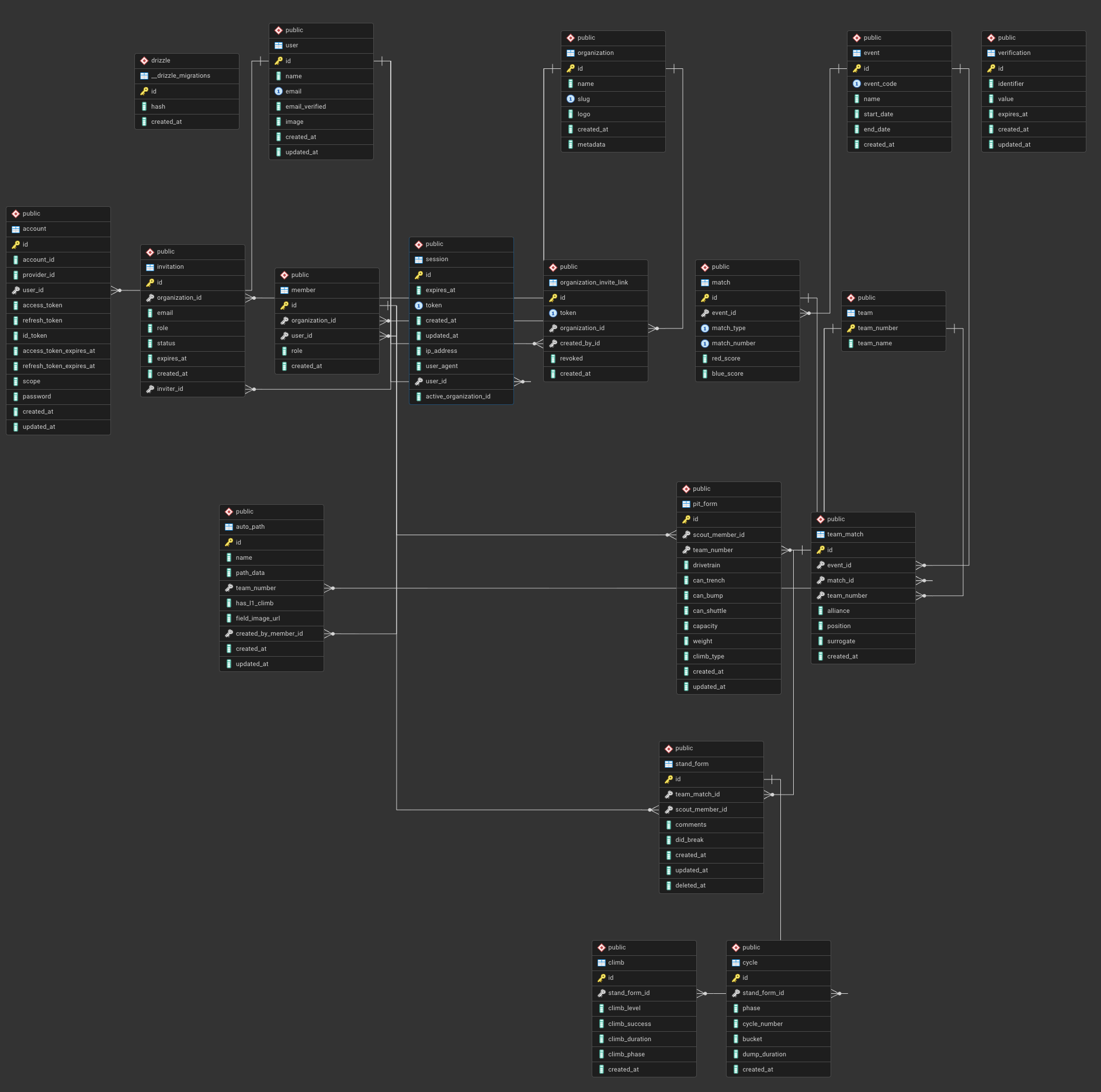

ERD (Entity Relationship Diagram) for the 2026 scouting site

In a relational database, tables are the core building blocks. Each table represents a single kind of thing your application cares about, and each row in that table represents one concrete instance of that thing.

For example, in a scouting application you might have tables for users, events, matches, teams, and scouting forms. Each of these tables stores data about exactly one concept, rather than mixing unrelated information together.

A table is made up of columns and rows. Columns define what attributes are stored (such as team_number, match_number, or created_at), and each row is a single record. This structure is similar to a spreadsheet, but unlike a spreadsheet, tables are designed to be linked together in a consistent and reliable way.

Looking at the ERD above, each box represents a table. The fields listed inside the box are the columns for that table, and the key icon indicates a primary key—usually an id—which uniquely identifies each row. These IDs are what allow other tables to reference a specific record.

For example, instead of storing a team’s name and number everywhere, other tables store a reference like team_number or team_id. A scouting form doesn’t need to duplicate team data; it simply points to the team it belongs to. This keeps the database organized and prevents inconsistencies.

The lines between tables represent relationships. They show how one table references another, such as a match belonging to an event, or a scouting form belonging to a specific team in a specific match. These relationships are what make relational databases powerful, and they allow you to ask meaningful questions like “show me all scouting data for this team at this event” without duplicating information.

As you read the ERD, a good mental model is:

-

Boxes are kinds of data

-

Rows are individual things

-

IDs are how tables point to each other

Understanding tables and how they relate is the foundation for writing useful queries and designing databases that scale beyond simple projects.

Modeling Tables

Designing a database is less about writing SQL and more about deciding how your data should be structured. This process is called modeling, and it’s where most good (or bad) database decisions are made.

When modeling tables, a useful rule of thumb is that each table should represent a single concept. In a scouting app, concepts might include teams, matches, events, users, or scouting entries. If a table starts to describe more than one thing at once, it’s usually a sign that it should be split apart.

A common beginner mistake is to store everything in one large table. While this may seem simpler at first, it quickly becomes difficult to maintain and leads to duplicated or inconsistent data. Relational databases are designed to avoid this by separating data into focused tables and connecting them with relationships.

Another important decision is what belongs in a table versus what should be referenced. Stable, reusable data—like teams, events, or users—should generally live in their own tables. More specific or temporary data—like a team’s performance in a single match—should reference those tables instead of duplicating their information. This is why a scouting form points to a team and a match, rather than storing the team’s name or event details directly.

Primary keys play a central role in modeling. Every table should have a primary key that uniquely identifies each row. Other tables can then store this key as a foreign key to create relationships. These IDs are internal to the database and should be treated as stable identifiers, even if other attributes change over time.

It’s also important to think about how the data will be queried. If you frequently need to answer questions like “show me all matches at this event” or “show me all scouting entries for this team,” your tables should reflect those relationships clearly. Good modeling makes queries straightforward; poor modeling pushes complexity into application code.

Finally, database models evolve. Early versions are rarely perfect, and it’s normal to adjust tables as requirements become clearer. The goal isn’t to predict everything up front, but to build a structure that is logical, consistent, and flexible enough to grow without collapsing under its own complexity.

Modeling tables well is what turns a database from a storage dump into a system you can reason about—and it’s one of the most valuable skills you can learn when building real applications.

No Comments